1617 Having “The Conversation” – Telling Your Advisor You Don’t Want to Be a Professor 1560 Three Keys for Graduate School Success 1552 Ph.D.s (and Advisers) Shouldn’t Overlook Community Colleges. Stanford-affiliated singles, aged 50+, socializing in casual environments. The Club sponsors a variety of activities such as Meet & Mingle, parties, dances, trips, and attendance at plays, concerts and exhibits. Weekly activities include tennis, hiking, and lectures. Non-members are welcome at most events. Online Dating in Stanford Kentucky, United States Loveawake is a top-performing online dating site with members present in United States and many other countries. Loveawake has over a million registered singles and over 1000 new men and women are joining daily. With all these statistics you are almost guaranteed to meet your Stanford match. Aug 21, 2019 Algorithms, and not friends and family, are now the go-to matchmaker for people looking for love, Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld has found. Online dating has become the most common way for Americans to find romantic partners. (Image credit: altmodern / Getty Images).

Now available:

- A totally new survey, HCMST 2017, fielded in the summer of 2017, with a fresh sample of 3,510 American adults, with lots of new questions about phone dating apps and other ways of meeting and dating. This new dataset is available on a separate page: https://data.stanford.edu/hcmst2017

How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST) is a study of how Americans meet their spouses and romantic partners.

- The study is a nationally representative study of American adults.

- 4,002 adults responded to the survey, 3,009 of those had a spouse or main romantic partner.

- The study oversamples self-identified gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults

- Follow-up surveys were implemented one and two years after the main survey, to study couple dissolution rates. Version 3.0 of the dataset includes two follow-up surveys, waves 2 and 3.

- Waves 4 and 5 are provided as separate data files that can be linked back to the main file via variable caseid_new.

The study will provide answers to the following research questions:

- Do traditional couples and nontraditional couples meet in the same way? What kinds of couples are more likely to have met online?

- Have the most recent marriage cohorts (especially the traditional heterosexual same-race married couples) met in the same way their parents and grandparents did?

- Does meeting online lead to greater or less couple stability?

- How do the couple dissolution rates of nontraditional couples compare to the couple dissolution rates of more traditional same-race heterosexual couples?

- How does the availability of civil union, domestic partnership or same-sex marriage rights affect couple stability for same-sex couples? This study will provide the first nationally representative data on the couple dissolution rates of same-sex couples.

Rosenfeld, Michael J., Reuben J. Thomas, and Maja Falcon. 2018. How Couples Meet and Stay Together, Waves 1, 2, and 3: Public version 3.04, plus wave 4 supplement version 1.02 and wave 5 supplement version 1.0 and wave 6 supplement ver 1.0 [Computer files]. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries.

The HCMST data are freely available to users who register with SSDS/ Stanford Libraries.

* Note [12/06/2011] data.stanford.edu has a new web server, so if you find that you old login and password do not work, please clear your browser cache and cookies and try again. Thanks, and sorry for any difficulties.

I acknowledge core funding support from the U.S. National Science Foundation, and supplementary funding from Stanford's Institute for Research in the Social Sciences, and the UPS endowment at Stanford University. For research assistance, I thank Reuben Jasper Thomas, Elizabeth McClintock, Esra Burak, Kate Weisshaar, Taylor Orth, Ariela Schachter, Maja Falcon, and Sonia Hausen. For Web design and assistance, I am grateful to Ron Nakao and the Stanford Library. The following consultants contributed to the development of the survey instrument and the research design: Gary Gates, Jon Krosnick, Brian Powell, Daniel Lichter, Matthijs Kalmijn, Timothy Biblarz, and the staff of Knowledge Networks/GfK.

The survey was carried out by survey firm Knowledge Networks (now called GfK). The survey respondents were recruited from an ongoing panel. Panelists are recruited via random digit dial phone survey. Survey questions were mostly answered online; some follow-up surveys were conducted by phone. Panelists who did not have internet access at home were given an internet access device (WebTV). For further information about how the Knowledge Networks hybrid phone-internet survey compares to other survey methodology, see attached documentation.

The dataset contains variables that are derived from several sources. There are variables from the Main Survey Instrument, there are variables generated from the investigators which were created after the Main Survey, and there are demographic background variables from Knowledge Networks which pre-date the Main Survey. Dates for main survey and for the prior background surveys are included in the dataset for each respondent. The source for each variable is identified in the codebook, and in notes appended within the dataset itself (notes may only be available for the Stata version of the dataset).

Respondents who had no spouse or main romantic partner were dropped from the Main Survey. Unpartnered respondents remain in the dataset, and demographic background variables are available for them.

See 'Notes on the Weights' in the Documentation section.

- The data I download from the Data Archive will not be used to identify individuals.

- I will not charge a fee for the data if I distribute it to others.

- I will inform the contact person for each dataset about work I do using their dataset.

(This helps us keep an accurate bibliography. See each data page for its contact email. ) - I will cite the data appropriately.

(See each data page for its bibliographic citation.)

Optional: enter your email address below to receive an email when data is updated.

Note for SPSS and SAS users: we have replaced the portable versions of the SPSS and SAS files with the .sav and .sas7bdat versions, respectively, to accommodate the long variable names in the dataset. The Stanford research team does all their work in STATA, so if you find discrepancies between the SAS or SPSS versions of the dataset and the documentation, please let us know. Thus far we have found that SPSS truncates value labels to 32 characters.

Current Data Version 3.04 plus wave 4 supplement, version 1.02, wave 5 supplement version 1.0, and wave 6 supplement version 1.0

Schedule of Future Additions to the HCMST dataset

- All 5 budgeted waves of HCMST have been completed and publicly posted.

- HCMST wave 6 was fielded in summer, 2017, and will be posted soon.

- HCMST 2017, a new study with fresh subjects, was fielded in the summer of 2017 and will be posted soon.

Forthcoming and restricted HCMST data

Restricted data:

- Disclosure of redacted full-text answers to q24 ('how couples meet') and q35 ('explain relationship quality'). Because of demand from users of HCMST, we have redacted the Q24 and Q35 text answers, and obtained IRB approval to share the redacted answers on a restricted basis. As of February, 2013, ICPSR is making the edited versions of full-text q24 and q35 available to researchers who get their own IRB approval to host the data. Contact ICPSR for access.

- We are planning (at a future date) to redact the text variables from waves 4 and 5 append them to the restricted data hosted by ICPSR.

- Geographic codes for ZIP code, as well as a variety of state-based variables, which have been suppressed from the public dataset in order to preserve respondent confidentiality, are available from ICPSR for users who obtain IRB approval.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q) There are a variety of different kinds of questions in the dataset about sexual identity, whether the respondent is part of a same-sex couple, and what gender of person the respondent is sexually attracted to. The answers to these questions sometimes seem to provide contradictory information. Why?

A) There is some inherent ambiguity in the realm of sexual identity and in identifying same-sex couples. There is also the possibility that a small number of respondents don't understand the questions. PI Rosenfeld created several new variables for the dataset, same_sex_couple, potential_partner_gender_recodes, alt_partner_gender. These new variables represent the researcher's best guess as to the gender of the partner, and as to whether the couple is a same-sex couple. In creating these variables PI Rosenfeld relied mostly on the variables in the public data, and a little bit on the text answers that are not part of the public data.

Q) What is the variable that identifies the partnered respondents?

A) qflag

Q) Why do the variables for children in the household (such as ppt01, ppt25, etc) not yield exactly the same information about household members as the household roster variables (such as pphhcomp11_member2_relationship)?

A) There are several reasons for the discrepancies. First, the ppt01 and ppt25 variables were derived from answers provided by the head of household, while the household roster variables were derived from the survey respondent. Not all survey respondents are the head of household as far as Knowledge Networks is concerned (see variable pphhhead). Second, household survey that was the source of the ppt01 and ppt** variables may not have taken place at the same time as the Core Adult Profile which was the source of the household roster variables such as pphhcomp11_member2_relationship. Lastly, the ppt01 and ppt** variables are incremented over time, as the children in the household are presumed to age over time. So the ppt** variables are accurate for the time of wave 1 of the HCMST survey, whereas the household roster variables are accurate reports from the time of the Core Adult Profile, which took place earlier.

Changes, additions, and improvements to the dataset

Changes for version 2.0

- Version 2.0 of the dataset includes new variables from wave II of the survey, the one year follow-up, along with the previously available variables from wave I, the main survey. See the new User's Guide under documentation for more information about variable layout.

- Version 2.0 also includes a second round of background demographic data for most respondents in the dataset, see User's Guide for variable layout.

- The Stanford research team has added a new variable, how_met_online, which categorizes the prior social connections (if any) between respondent and partner for respondents who met their partners online, based largely on an exhaustive re-analysis of the respondents open text answers to q24 (the open text answers are not yet available in the public dataset for respondent confidentiality reasons). See also the new variable either_internet_adjusted .

- Version 2.0 includes a new couple weight, weight_couples_coresident, see the updated documentation on weights for more details.

- For version 2.0 the Stanford research team has added two new date variables in YYYYMMDD format, HCM_main_interview_fin_date and w2_HCM_interview_fin_date. These variables are easier to read but less useful for analysis than the other date-time format variables already in the dataset.

- The variable partner_deceased has been updated to reflect the discovery of a few more cases of respondents whose partner was already deceased at the time of the main survey.

Changes from version 2.0 to version 3.02

- Version 3 includes wave 3 of the survey (the second follow-up survey) variables generally starting with w3_*, along with the third round of core adult profile data, variables generally starting with pp3_*

- New variables describing the particular family members who played the intermediary role in respondent meeting partner, variables coded q24_fam*

- The documentation for earlier versions offered a not-quite correct explanation for the variable ppnet. ppnet actually codes whether subject had their own internet access at home at the time of the profile survey, so this can change with each wave of the KN profile survey, so each profile survey will carry new versions of ppnet (see pp2_ppnet and pp3_ppnet).

- Stanford research team decided to include newer versions of profile data for subjects’ race, and education with each new wave of profile data; see for instance pp2_ppeduc, pp3_ppeduc.

- Variable q18a_3 label and description were clarified.

- Variable w2_xss label and description were clarified.

- Labels for how_long_ago_first_met, how_long_ago_first_cohab, etc were clarified to make clear that the unit is years.

- re-coded the w2_broke_up and the w3_brokeup_actual to distinguish between break-up and partner deceased.

- Added variables for interstate moves by subjects between pp1, pp2, and pp3, see for instance interstate_mover_pp1_pp2

- Many clarifications to documentation and variable and value labels

Research Papers Using HCMST

* Rosenfeld and Thomas 2012, Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary, published in the August, 2012 American Sociological Review 77 (4) 523-547 Or link to the pre-typeset version here.

* Thomas, 2011 How Americans (mostly don't) Find an Interracial Partner, working paper.

* Rosenfeld, 2014, Couple Longevity in the Era of Same-Sex Marriage in the US, Journal of Marriage and Family 76: 905-918

* Weisshaar, Kate, 2014, 'Earnings Equality and Relationship Stability for Same-Sex and Heterosexual Couples,' Social Forces 93(1): 93-123.

* Falcon, Maja, 2015, 'Family Influences on Mate Selection: Outcomes for Homogamy and Same-Sex Coupling' , working paper.

* Schachter, Ariela, 2015, 'Measurement Error in Panel Data: A Comparison of Face-to-Face and Internet Survey Samples' , working paper.

* Rosenfeld, 2015, 'Who Wants the Breakup? Gender and Breakup in Heterosexual Couples' , forthcoming in an edited volume Social Networks and the Life Course.

* Rosenfeld, 2017, 'Marriage, Choice and Couplehood in the Age of the Internet.' Published in Sociological Science, 4: 490-510.

* Rosenfeld, 2017, 'How Tinder and the dating apps Are and are Not Changing dating and mating in the U.S,' conference paper.

* USA Today, Feb 11, 2010 story by Sharon Jayson on friends, the Web, and How Couples Meet

* Stanford Report, Feb 11, 2010 a feature story on How Couples Meet, with video

* San Jose Mercury News, Feb 14, 2010 Growing Number of Singles Find Their Valentines Online (link currently unavailable).

* NPR, 'Computers are Becoming Cupid's Best Weapon,' story by Jennifer Ludden August 16, 2010

* Reuters Newswire Being Online can Boost Your Chances of Being In Love , August 16, 2010

* Radio Nacional de Colombia story , August 16, 2010

* The Economist story 'Love at First Byte', December 29, 2010.

* The Discovery Chanel story 'Does Online Dating Work?', February 11, 2011

* The ABC News version of the Discovery Chanel Story Here, from February 12, 2011

* A New York Times article on online dating 'Love, Lies and What They Learned' , from November 12 (online) and November 13 (print), 2011.

* Aziz Ansari and Eric Klinenberg's 2015 book, Modern Romance, draws usefully on the changing way couples meet, based on findings from the How Couples Meet and Stay Together dataset, and on the analyses in the Rosenfeld and Thomas 2012 American Sociological Review paper. See also the June, 2015 Time Magazine online story by Ansari and the June 14, 2015 Ansari and Klinenberg opinion piece on online dating in the New York Times.

* More recent links to press coverage of the HCMST project can be found on the press links page at Rosenfeld's Stanford website, here.

Stanford Your Dating Site

Matchmaking is now done primarily by algorithms, according to new research from Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld. His new study shows that most heterosexual couples today meet online.

By Alex Shashkevich

Algorithms, and not friends and family, are now the go-to matchmaker for people looking for love, Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld has found.

Online dating has become the most common way for Americans to find romantic partners. (Image credit: altmodern / Getty Images)

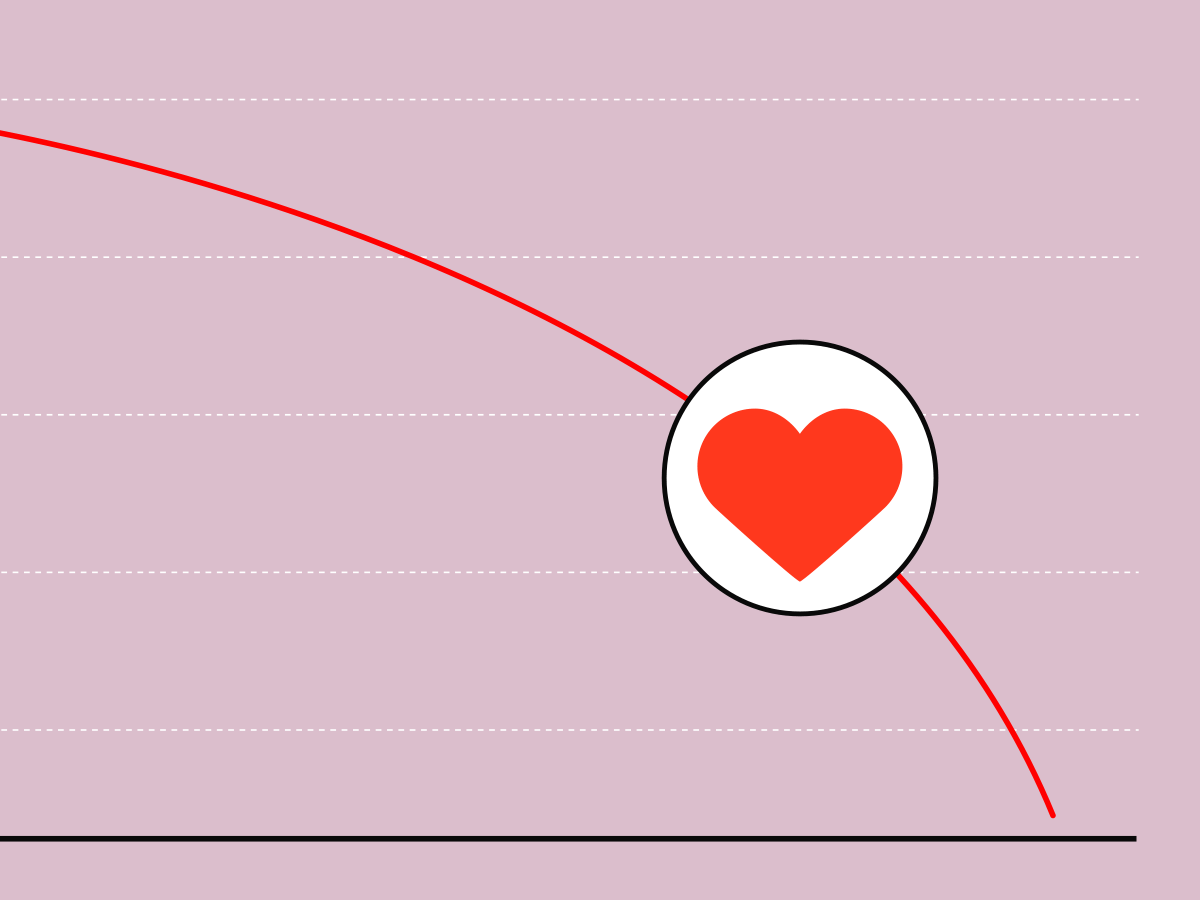

In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Rosenfeld found that heterosexual couples are more likely to meet a romantic partner online than through personal contacts and connections. Since 1940, traditional ways of meeting partners – through family, in church and in the neighborhood – have all been in decline, Rosenfeld said.

Rosenfeld, a lead author on the research and a professor of sociology in the School of Humanities and Sciences, drew on a nationally representative 2017 survey of American adults and found that about 39 percent of heterosexual couples reported meeting their partner online, compared to 22 percent in 2009. Sonia Hausen, a graduate student in sociology, was a co-author of the paper and contributed to the research.

Rosenfeld has studied mating and dating as well as the internet’s effect on society for two decades.

Stanford News Service interviewed Rosenfeld about his research.

What’s the main takeaway from your research on online dating?

Stanford Your Dating Site App

Meeting a significant other online has replaced meeting through friends. People trust the new dating technology more and more, and the stigma of meeting online seems to have worn off.

In 2009, when I last researched how people find their significant others, most people were still using a friend as an intermediary to meet their partners. Back then, if people used online websites, they still turned to friends for help setting up their profile page. Friends also helped screen potential romantic interests.

Free Dating Sites No Fees

What were you surprised to find?

I was surprised at how much online dating has displaced the help of friends in meeting a romantic partner. Our previous thinking was that the role of friends in dating would never be displaced. But it seems like online dating is displacing it. That’s an important development in people’s relationship with technology.

What do you believe led to the shift in how people meet their significant other?

There are two core technological innovations that have each elevated online dating. The first innovation was the birth of the graphical World Wide Web around 1995. There had been a trickle of online dating in the old text-based bulletin board systems prior to 1995, but the graphical web put pictures and search at the forefront of the internet. Pictures and search appear to have added a lot to the internet dating experience. The second core innovation is the spectacular rise of the smart phone in the 2010s. The rise of the smart phone took internet dating off the desktop and put it in everyone’s pocket, all the time.

Also, the online dating systems have much larger pools of potential partners compared to the number of people your mother knows, or the number of people your best friend knows. Dating websites have enormous advantages of scale. Even if most of the people in the pool are not to your taste, a larger choice set makes it more likely you can find someone who suits you.

Does your finding indicate that people are increasingly less social?

No. If we spend more time online, it does not mean we are less social.

When it comes to single people looking for romantic partners, the online dating technology is only a good thing, in my view. It seems to me that it’s a basic human need to find someone else to partner with and if technology is helping that, then it’s doing something useful.

The decline of meeting partners through family isn’t a sign that people don’t need their family anymore. It’s just a sign that romantic partnership is taking place later in life.

In addition, in our study we found that the success of a relationship did not depend on whether the people met online or not. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how you met your significant other, the relationship takes a life of its own after the initial meeting.

Stanford Your Dating Site Website

What does your research reveal about the online world?

Stanford Your Dating Site Officiel

I think that internet dating is a modest positive addition to our world. It is generating interaction between people that we otherwise wouldn’t have.

People who have in the past had trouble finding a potential partner benefit the most from the broader choice set provided by the dating apps.

Internet dating has the potential to serve people who were ill-served by family, friends and work. One group of people who was ill-served was the LGBTQ+ community. So the rate of gay couples meeting online is much higher than for heterosexual couples.

You’ve studied dating for over two decades. Why did you decide to research online dating?

The landscape of dating is just one aspect of our lives that is being affected by technology. And I always had a natural interest in how new technology was overturning the way we build our relationships.

Stanford Your Dating Sites

I was curious how couples meet and how has it changed over time. But no one has looked too deeply into that question, so I decided to research it myself.